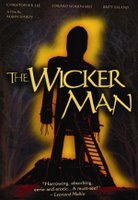

The Wicker Man (1973)

Horror in The Wicker Man comes equally from those qualities that forsake genre conventions as it does those that emulate them. Exposed here are the barbarities of the human action in the name of religion, of the damning power of intolerance. Taken at face value, religion is but a set of unverifiable answers to a series of unanswerable questions; belief in the unknown can indeed be a comforting approach to take to many of life’s troubles, but look no further than the Crusades, slavery, the WTC attacks and everything thereafter to see but a fraction of what has been committed in the name of religion. The Wicker Man assumes a more specific, but equally damning, approach to this notion, employing a deceptively typical whodunit narrative only to blindside the viewer with the unexpectedly inhumane yet perfectly consequential climax. The film may be bloodless, but at a humanitarian level it trumps even The Passion of the Christ in its ability to disturb (in this case, too, these troubling qualities are productive – rather than reductive – in nature).

Horror in The Wicker Man comes equally from those qualities that forsake genre conventions as it does those that emulate them. Exposed here are the barbarities of the human action in the name of religion, of the damning power of intolerance. Taken at face value, religion is but a set of unverifiable answers to a series of unanswerable questions; belief in the unknown can indeed be a comforting approach to take to many of life’s troubles, but look no further than the Crusades, slavery, the WTC attacks and everything thereafter to see but a fraction of what has been committed in the name of religion. The Wicker Man assumes a more specific, but equally damning, approach to this notion, employing a deceptively typical whodunit narrative only to blindside the viewer with the unexpectedly inhumane yet perfectly consequential climax. The film may be bloodless, but at a humanitarian level it trumps even The Passion of the Christ in its ability to disturb (in this case, too, these troubling qualities are productive – rather than reductive – in nature).Arriving on a secluded island (“famous for its fruit and vegetables”) after an anonymous report concerning a missing girl, Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) quickly undergoes a state of massive culture shock. Raised an ardent Christian and still an unmarried virgin, the open frankness towards sexuality (schoolgirls discuss the phallic symbol as a regular lesson) and public copulation – both common and somewhat expected behaviors in the village – only enrage him further when he discovers that his own religion is studied as but an “alternative” in the region. His unshakable faith is upset by his inability to imagine it coexisting with any other (and a generally defensive, power-hungry attitude to boot), although his suspicions of foul play and potential murder aren’t completely unfounded (eerily foreshadowed by Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle, his own personal favorite role, this being his favorite film of all he ever partook in). If the mystery surrounding the affairs on the island feel somewhat contrived, that’s largely the point: Howie is so absorbed with defending his own life choices (by means of denouncing others) that he fails to see the larger picture before it is too late.

The sexual practices of the village are certainly uneasy but nonetheless grounding in a recognizable reality; only when their religious practices begin to reveal themselves (during the climactic May Day celebrations) does the culture shock transpose itself onto the viewer. They appear as any religious practices would appear to an outsider, but while their pagan rituals (heavily characterized by nudity and a use of animal imagery) are atypically bizarre on the surface, the kinship they share with even familiar religious behaviors is what lends them their most internally dreadful qualities. The film’s austere visual compositions and loose framing increases this sense of a familiar-yet-unfamiliar setting, only for the potent images to take peel back the layers of meaning as the truly terrible truths lurking behind the surface of things reveal themselves. The film shares more in common with Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery" than anything even remotely close to the slasher genre, which is to say that it’s more profoundly disturbing than any amount of bloodletting could hope to be. In the end, it makes one of the best cases for taking up atheism imaginable.

Note: This review concerns the 88-minute theatrical version of the film, specifically.

Feature: Horror Marathon 2006