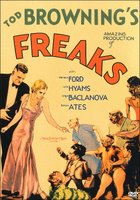

Freaks (1932)

That Freaks is generally considered a member of the “horror” genre is telling in ways that both reinforce the film’s central themes – thus validating them even further – as well as obscure them from being fully understood and appreciated. How this scale tips may very well depend on the viewer in question; truly, those who take it as being horrifying based on its surface alone are likely the very members of society the film rightfully criticizes. Commissioned by MGM to create a film even more horrifying than Universal’s immensely successful Frankenstein (as well as his own Dracula), Tod Browning crafted a film about and starring the physically impaired and handicapped – many of them real sideshow freaks whose careers up until the film had been spent traveling with the circus only for their physical nature to be gawked and laughed at. The film would bring them little fame in their lifetime; deemed too shocking, horrifying, and obscene, it vanished almost instantly from circulation. While Browning’s career would never recover, what remains is one of the most humane and sympathetic films ever made, a fact that makes it’s own persecution throughout the decades that much more ironic.

That Freaks is generally considered a member of the “horror” genre is telling in ways that both reinforce the film’s central themes – thus validating them even further – as well as obscure them from being fully understood and appreciated. How this scale tips may very well depend on the viewer in question; truly, those who take it as being horrifying based on its surface alone are likely the very members of society the film rightfully criticizes. Commissioned by MGM to create a film even more horrifying than Universal’s immensely successful Frankenstein (as well as his own Dracula), Tod Browning crafted a film about and starring the physically impaired and handicapped – many of them real sideshow freaks whose careers up until the film had been spent traveling with the circus only for their physical nature to be gawked and laughed at. The film would bring them little fame in their lifetime; deemed too shocking, horrifying, and obscene, it vanished almost instantly from circulation. While Browning’s career would never recover, what remains is one of the most humane and sympathetic films ever made, a fact that makes it’s own persecution throughout the decades that much more ironic.A lean 64 minutes, Freaks is a testament to cinematic efficiency (although some of the original cut is now lost, it doesn’t detract in any noticeable way), but more crucial is its un-exploitative observation of its titular characters. The setting: the tightly-knit community of a circus’ sideshow, where life goes on as normal despite seemingly devastating handicaps and diseases (such as absent limbs, stunted growth, multiple genders, and one boy missing everything below the stomach). Observed going about their daily activities – eating, drinking, playing, loving, and, in one amazing scene, lighting a cigarette – their physical limitations couldn’t seem more natural, and indeed fade into the background so as to let their unaltered humanity shine through without impairment. Yet the beautiful trapeze artist Olga Baclanova (perhaps an unintended surrogate for 1932 audiences?), herself without any bodily deformations, can only see the sideshow members as amusing oddities, and certainly less than human. Her cruel toying with the smitten midget Hans (Harry Earles) takes on new levels of heinousness when she learns of the fortune he’s inherited; she quickly marries him, only to slip poison into his champagne during the post-ceremony dinner.

Her actions earn swift retribution upon their discovery; the “freaks” operate as a single unit, with an offense to one being treated as universal (the film being told in flash-back, framed by a sideshow exhibit featuring a post-mutilation Olga). In what is arguably the film’s most terrifying sequence (set during a relentless rainstorm), Olga’s cohort (and lover) Hercules (Henry Victor), mortally stabbed, attempts to escape the steadily encroaching, bloodthirsty sideshow actors amidst the muddy ground beneath the circus wagons. Here, all are on equal footing, the deformed lot capable of just the same hateful and malicious acts as their fully functional counterparts – just as they share the same capacities for love and happiness. More famous is the film’s “one of us” montage, where, during the wedding ceremony, the sideshow troupe indicts Olga into their ranks via a repeated chant; horrified of being considered their equal, and too intoxicated on spirits to conceal her true feelings (Mel Gibson anyone?), she hatefully lashes out at them and their physical differences. Thus, the true horror of the film comes not from the physical appearances of its characters, but its antagonists’ incapacity to accept that which is different, and the unwaveringly universal capability of all men to act out of ill will and with violence.

Feature: Horror Marathon 2006