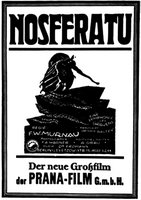

Nosferatu (1922)

The vampire feature found its first incarnation with F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, an unofficial adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula. That title, however, almost saw the entire film destroyed. Stoker’s widow, to whom royalties on his works went, easily saw through the film’s changing of names whilst adapting virtually the same plot, and sued for compensation, the court’s ruling being that every copy of Nosferatu had to be destroyed. Thankfully, evasion of the law proved an artistic triumph and a means of preserving a landmark work. Nosferatu, paired with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, is one of the hallmark foundations of the German expressionist movement (albeit here of a more eerily natural kind than the obtuse set designs of Weine’s predecessor). It is often regarded as the greatest vampire movie ever made (an assertion I do not support, although I don’t believe it’s far off), but regardless of its overall ranking, it is certainly one of the most subtly festering horror films ever made.

The vampire feature found its first incarnation with F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, an unofficial adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula. That title, however, almost saw the entire film destroyed. Stoker’s widow, to whom royalties on his works went, easily saw through the film’s changing of names whilst adapting virtually the same plot, and sued for compensation, the court’s ruling being that every copy of Nosferatu had to be destroyed. Thankfully, evasion of the law proved an artistic triumph and a means of preserving a landmark work. Nosferatu, paired with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, is one of the hallmark foundations of the German expressionist movement (albeit here of a more eerily natural kind than the obtuse set designs of Weine’s predecessor). It is often regarded as the greatest vampire movie ever made (an assertion I do not support, although I don’t believe it’s far off), but regardless of its overall ranking, it is certainly one of the most subtly festering horror films ever made.Every image and composition of Nosferatu suggests a half-dead world, the rotting, decomposing corpse of which Murnau obsessively examines with his camera. All seems to have been stillborn, the efforts of the human characters among the only remaining rays of light amidst the darkness; selflessness is ultimately the saving grace of a world otherwise gone to hell. The story is familiar to most; a retail salesman, Thomas (Gustav von Wangenheim), travels to Transylvania to complete a transaction with the wealthy Count Orlock (Max Schreck – German for “maximum terror,” ironically – or, a la Shadow of the Vampire, perhaps not), unperturbed by the warnings from the superstitious locals. Quickly, he learns that the vampire folklore is indeed a serious manner, but not before the Count is the official owner of a home in Thomas’ German hometown. An ill Thomas (sick with a fever induced by the predator Count) rushes home to protect his wife Ellen, but not before Orlock arrives first, bringing with him a deadly plague that begins to eradicate the population.

Horror is almost a misnomer for Nosferatu. Frightening in an existential and spiritual way it surely is, but the effect of the film is not the visceral high generally expected of the genre but the trance-inducing tone more typical of a mood piece. A lingering gaze on natural imagery lends the film this quality, its horror encapsulated not so much in the strictly supernatural (as is evident via the happenings surrounding Count Orlock) as it is ingrained in the monolithic qualities of the natural world. Count Orlock, however, is anything but natural, his distorted features more closely resembling a nimble, upright walking, albino rat than anything that could be called remotely human. His plight is perhaps the saddest of all those in the film, the eternally isolated life of the vampire portrayed as a plague in itself, thus forging a theme that has continued to recur within the genre since this first appearance.

At the center of the film is Schreck’s rightfully revered performance, one so understated and absorbed into the film that it is impossible to imagine the work as a whole without it. Orlock’s body language and physical features create a figure of interlocking contradictions, the former not unlike a gothic ballet interpretation and the latter deeply expressive through its exaggerated repulsiveness. Orlock’s physical presence is not unlike the shadowy representations employed throughout the film; perhaps no single image is more transfixing than the shadow of Count Orlock reaching for the door separating him from his innocent victim. At one point in the film, a scientist points out how a carnivorous hydra plant is so transparent that the physical being is almost nonexistent; so too does Orlock’s body occupy a realm that moves beyond the flesh only to penetrate into the world of the spirit. While the majority of its imitators would define vampirism solely through the physical role of stakes, garlic, blood, and holy water, Nosferatu taps into the psychosexual longings of its mythology with primal efficiency and a somber, platonic aftertaste.

Feature: Horror Marathon 2006