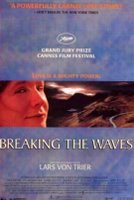

Breaking the Waves (1996)

My chief concern with this review is that it might fail in giving the movie in question enough credit, so let me abandon any sense of subtlety for a moment and lay it out in simple terms: Lars Von Trier's Breaking the Waves is the best film I have yet seen from the 1990’s. Influenced by – but not in complete accordance with the rules of – the Dogme 95 cinematic movement co-founded by von Trier himself, the film takes a relatively simple story and reinvigorates its potential by stripping its technical qualities down to the bare, earthly elements. We’ve seen this sort of tale before, from Hollywood classics to Oscar-tailored hackwork to Lifetime movies of the week, but never with as much pulsing life force as exhibited here. Of course, one could hotly debate that Emily Watson is the chief reason for the films’ success (I’m more of a parts-to-the-whole onlooker than one who singles out specific elements), her performance as the naïve but loving and faithful Bess McNeill one of magnificent range and staggering emotional potential. No offense, Francis, but you can’t hold a candle.

My chief concern with this review is that it might fail in giving the movie in question enough credit, so let me abandon any sense of subtlety for a moment and lay it out in simple terms: Lars Von Trier's Breaking the Waves is the best film I have yet seen from the 1990’s. Influenced by – but not in complete accordance with the rules of – the Dogme 95 cinematic movement co-founded by von Trier himself, the film takes a relatively simple story and reinvigorates its potential by stripping its technical qualities down to the bare, earthly elements. We’ve seen this sort of tale before, from Hollywood classics to Oscar-tailored hackwork to Lifetime movies of the week, but never with as much pulsing life force as exhibited here. Of course, one could hotly debate that Emily Watson is the chief reason for the films’ success (I’m more of a parts-to-the-whole onlooker than one who singles out specific elements), her performance as the naïve but loving and faithful Bess McNeill one of magnificent range and staggering emotional potential. No offense, Francis, but you can’t hold a candle.The opening scene finds Bess asking her local church elders (to whom, after God, she has always been most committed) for permission to marry her love, Jan (Stellan Skarsgård), who works on an oil rig north of her Scotland home. Permission is granted, hesitantly, and Bess’ best friend Dodo (Katrin Cartlidge) openly expresses her initial distrust to the new husband. (spoilers herein) Bess’ regular, open prayers to God do little to ease her pain when Jan has to leave again to work, and when Jan comes back early from a devastating neck injury after Bess asks God to bring him home, she sees herself to blame for his potentially paralyzing accident. Through her selfless dedication to God and Jan, Bess believes herself to be the only one who can save Jan; perhaps due to overmedication and hallucinations, the nearly crippled Jan asks Bess to make love to other men so that the stories of her endeavors might keep him alive longer. The more his condition worsens, the more desperate and dangerous her behavior becomes. All in the name of love.

As someone who knows people who have a hard time separating the concepts of religion and faith, it’s nothing short of my own little miracle to come across a film with such a boundless sense of the latter while also mercilessly indicting the hatred so often present in more fundamentalist brands of organized worship. At Bess’ church, woman can neither talk nor attend the burial during funerals, and after the wedding ceremonies, one of Jan’s rig buddies remarks how dull it is to have a church with no bells. The God Bess looks to and that which her church imagines are two distinctly different entities, and it’s not hard to guess which one ultimately provides her with redemption in the darkest of hours (long after her family and community have turned their backs). The film’s cumulative emotional wallop (during which my emotional display was nothing short of violent) is inseparable from its no-bullshit aesthetic; shot on video and transferred to film, the stark, grainy look lends itself to human emotion infinitely more than polished production values. The end result is an awe-inspiring testament to the power of life over death, of goodwill in the face of despair, and of love of a higher good in the face of earthly oppression. Even the bells of heaven would toll for a girl like Bess.