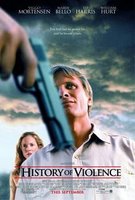

A History of Violence (2005)

Life in a rural American town is almost too good to be true in David Cronenberg's A History of Violence, which posits the glossy sheen of its close-knit community against the personal and familial tribulations brought about by the undoing of a false identity maintained by one of its residents. Behind the purported behaviors and attitudes of both townsfolk and family members lie unexpressed feelings and hidden truths, whether they're actually conscious of it or not. While the film doesn't quite suggest that the American dream on display is all image and no substance, it makes it perfectly clear that all is not what it seems.

Life in a rural American town is almost too good to be true in David Cronenberg's A History of Violence, which posits the glossy sheen of its close-knit community against the personal and familial tribulations brought about by the undoing of a false identity maintained by one of its residents. Behind the purported behaviors and attitudes of both townsfolk and family members lie unexpressed feelings and hidden truths, whether they're actually conscious of it or not. While the film doesn't quite suggest that the American dream on display is all image and no substance, it makes it perfectly clear that all is not what it seems.Take, for instance, Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen), loving husband, father of two, and esteemed business owner in his hometown of Millbrook, Indiana. When a pair of nomadic thugs hold up his diner one evening and threaten the lives of he and his customers, Tom's responsiveness, which finds both criminals dead by gunshot, is both deft and instinctive. Tom's skill with a firearm earns him the status of a local hero, an unfortunate fact when mobsters from Philadelphia show up at his diner and home, prompted by Tom's newfound popularity in the media. They know him as Joey Cusack, member of the Philadelphia mafia until he disappeared in the midst of bloodshed, changed his identity and set up a new life over a decade ago. Quickly, the structural basis for the life of both Tom and his family erodes away.

The malleable nature of identity is the life blood of A History of Violence, but the shock waves that register after Tom's past is revealed are the most compelling of its elements. Deceptively, the film's first act establishes the happiness of Tom's current life, only to be subjected to an existential schism when the past catches up with him. "I thought I killed Joey," pleads a torn Tom to Edie (Maria Bello), his distraught wife, upon his inability to maintain his guise any longer. The man she loves so deeply is still the same person, but her perception of him requires a complete overhaul, causing her to be simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by the muddled persona that happens to be her husband (most prominently displayed in a scene of spontaneous marital sex, at once loving, carnal and harboring intense resentment). We have no reason to question Tom's love for his family or the purity of his motives for starting his life over, but a responsibility for his past remains nonetheless, if only because who his is now is inseparable from who he once was.

Cronenberg's attentiveness to composition should come as no surprise, but that makes the film's visual reflection of its moods and relationships no less noteworthy. Everyday structures - a counter, a table, a curtain - act as signifiers of emotional disconnect, while the loaded shotgun in the Stall family living room, hastily removed from the closet, represents the uncovering of the past in response to present trauma. Meanwhile, paralleling more overly political cinematic dissertations on violence from this past year (Munich, Paradise Now), Tom is forced to tap into his otherwise repressed violent instincts in order to himself survive as well as to preserve the safety of his family, a trait handed down to his bullied son in typical ancestral fashion. Once out in the open, however, it doesn't take long for that same violence to turn inward, which is were the film's sense of ongoing struggle, long after the credits are over, finds its most potent outlet.

A History of Violence's rigorously intimate framing - positioning individuals as if we're only allowed to see what they choose to show - would be next to worthless without the affecting nature of its many complex, excellent performances. Maria Bello is the most immediately recognizable as a stricken and confused wife, devolved from someone without an ounce of concern as to the stability of her surroundings. Mortensen, on the other hand, has been unfairly overlooked for his skills; his performance is less boldly stated, but that's also because his character is in effect an actor as well, the multiple layers of his persona evident in his uneasy efforts at maintaining his behavioral camouflage, counteracted by his instinctive reactions to danger that betray his better efforts. In a final act appearance (so brief it just misses qualification as a cameo), John Hurt is perhaps provides what is perhaps the film's most savory performance, creating a wonderful character performance that makes this viewer wish an offshoot sequel were made for his persona alone.

Despite being named in the title, the violence in the film is less important thematically than it is as a means of disarming the audience with its horrific realism; shot through the back of his head, one of the would-be criminals at Tom's diner lies in a pool of his own blood, his jaw mangled, still half-conscious. By refusing to diminish the visual impressions Tom's actions leave, the film simultaneously removes the violence's typical quality of providing visceral entertainment as well as underscoring the scars that violence can leave on a family and community, whether through their occurrence in the present or their presence in history. While not as emotionally wrenching as, say, The Fly, the film continues to showcase Cronenberg's masterful knack for showing us those aspects of ourselves towards which we bear a natural aversion to. Through its restrained observation, A History of Violence peels away the layers we see daily to find the haunting truths concealed beneath.

Pretty good flick.....but i have to say that at the very beginning i had some serious doubts. When the little girl wakes up from a bad dream and the ENTIRE family comes in to comfort her, I thought I had mistakenly picked up The Brady Bunch instead. I expected Alice the housekeeper to float in with warm milk and cookies at any minute.

Luckily the film redeemed itself, and John Hurt's performance was truly masterful and one of the funniest of the year IMO.

Posted by Anonymous |

3:37 PM

Anonymous |

3:37 PM