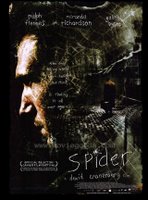

Spider (2002)

Spider refers to both the main character's nickname and the thematic essence of David Cronenberg's feature, in which the camera functions as a psychological signifier, reflecting and amplifying the twisted mental state of its subject. By means of deceptively simple visual signifiers, compositions, and camera movements, Spider creates a smooth, angular perception of the world not unlike the finely woven web of a spider itself. This puzzle-like rhythm finds physical manifestation in at least two scenes in the film; it is from these many fractured yet interconnected pieces that the viewer, like Spider himself, must find meaning in and ultimately put their sense of reality back together.

Spider refers to both the main character's nickname and the thematic essence of David Cronenberg's feature, in which the camera functions as a psychological signifier, reflecting and amplifying the twisted mental state of its subject. By means of deceptively simple visual signifiers, compositions, and camera movements, Spider creates a smooth, angular perception of the world not unlike the finely woven web of a spider itself. This puzzle-like rhythm finds physical manifestation in at least two scenes in the film; it is from these many fractured yet interconnected pieces that the viewer, like Spider himself, must find meaning in and ultimately put their sense of reality back together.Unlike the sickeningly literal and overwrought direction of A Beautiful Mind, Spider feels from start to finish as if all hangs by a thread. This is appropriate, considering that David 'Spider' Cleg has just been released to a halfway house from his stay at the insane asylum. We immediately sense that all has not been well for Mr. Cleg for some time, but now, even more so, seemingly everyday experiences and objects trigger locked-away memories and anxieties, forcing Spider to revisit his past in ways both literal and psychological. The connection between the traumas of the past and the events of the present are achieved through simple directorial touches and unheralded, effects-less walks down memory lane, in which Spider watches his past unfold in the presence of his parents and 9-year-old self (think of Harry Potter's trips through the Pensieve without all the fancy visual flourishes). These scenes embellish the roots of his frightened tendencies and discomfort with the female gender with understated efficiency. Fearing his father's abusive behavior towards his mother, young Spider withdraws into a world driven by a variation on the Oedipal complex. However, it isn't long before what has been accepted as reality reveals itself as an unexpected "yellow wallpaper" scenario.

Silently fractured and presented, it is these many pieces of the narrative that make up the confusing world of Mr. Cleg, although attention is all that is needed to put them back together as they slowly reveal themselves. Silent yet progressive, Spider subjects the viewer to the unfolding events as both an outside observer as well as through Spider's own perceptions. If A Beautiful Mind plays its psychological fantasies as a dramatic thrill ride before the ultimate plot-twisting pivot point, then Spider immerses the viewer in a state of tragic limitation before the revealing, tragic conclusion. These revelations serve to unify the audience and Spider, both drawing upon the same knowledge and both experiencing the same enlightenment simultaneously. Sharing this quality, Spider proves the antithesis to Ron Howard's Oscar-winner, nursing the emotional connection between the viewer and Spider rather than jerking them around like a flimsy dramatic roller coaster.

Cronenberg's films are known for their tendency to instill discomfort in the viewer by means of their intent look at those aspects of human nature we'd generally prefer to turn a blind eye to. Spider, in it's meditations on perception and insanity, satisfies this definition, but differs from the bulk of his works by means of its incredibly minimalist construction (as well as a noticeable lack of "squishy body" elements, a la Jeff Goldblum's physical transformation in The Fly). While Cronenberg's direction keeps the aesthetic respectful and sympathetic towards Spider's state (unlike Ron Howard, who prefers to capitalize on these disorders for cheap dramatic tricks), it is ultimately Ralph Fiennes' wonderful performance that creates the film's emotional backbone, which runs through like an invisible current. Spider is both ugly and off-putting, but bears a child-like innocence that makes his plight all the more sorrowful, lining the film with a sense of redemptive optimism amidst the predominant misanthropy. Incredibly rewarding and deeply humane, Spider may not be Cronenberg's best film, however, its contrasting tones and style proves his status as a master even when working outside his usual realm.