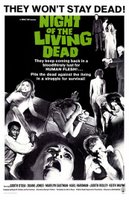

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

“They’re coming to get you, Barbra,” taunts the belligerent Johnny, well aware of his sisters’ innate fear of cemeteries – nighttime encroaching, no less – amidst whiny complaints of his own about the tedious process involved in visiting their father’s grave site and the three-hour drive home that awaits them. His disrespect of the dead quickly catches up with him, when the lurking individual he referenced actually attacks his sister and subsequently knocks him out cold, Barbra fleeing to a nearby deserted farm house before suffering a complete nervous breakdown. Night of the Living Dead was a shockwave of culturally lined horror when it first circulated nickelodeon theaters in 1968, and like any great work, it has allowed us to endlessly reinterpret it with new eyes ever since. What was once a pale allegory for 60’s racism can now be seen as America’s political failures after September 11th, 2001 (in that it turned inward on itself with xenophobic zeal rather than addressing the real problems at hand), no small achievement for a low-budget horror flick made in the outskirts of Pittsburgh.

“They’re coming to get you, Barbra,” taunts the belligerent Johnny, well aware of his sisters’ innate fear of cemeteries – nighttime encroaching, no less – amidst whiny complaints of his own about the tedious process involved in visiting their father’s grave site and the three-hour drive home that awaits them. His disrespect of the dead quickly catches up with him, when the lurking individual he referenced actually attacks his sister and subsequently knocks him out cold, Barbra fleeing to a nearby deserted farm house before suffering a complete nervous breakdown. Night of the Living Dead was a shockwave of culturally lined horror when it first circulated nickelodeon theaters in 1968, and like any great work, it has allowed us to endlessly reinterpret it with new eyes ever since. What was once a pale allegory for 60’s racism can now be seen as America’s political failures after September 11th, 2001 (in that it turned inward on itself with xenophobic zeal rather than addressing the real problems at hand), no small achievement for a low-budget horror flick made in the outskirts of Pittsburgh. Those who prefer their horror dealt out as formally as possible might take Night of the Living Dead as camp, but what frightens us most often has that slightly unreal quality, and between its completely un-subtle scoring and sporadic use obtuse camera angles, Night approximates these fears more than efficiently. Barbra is the initial audience surrogate; we may have seen the title of the film, but we know no more than the characters do in regards to what the hell is happening. For her, the unfolding events represent the manifestation of her deepest childhood fears, and for us there is a retroactive similarity to September 11th, with the surviving humans crowding around the television and radio eagerly awaiting updates on the situation (one begs the question: would the Bush administration be able to handle a zombie epidemic, or would we all be as supremely fucked as New Orleans?). But even without these real-world parallels, Night of the Living Dead works its purebred terror without mercy. Says Roger Ebert in his initial coverage of the film: “The kids in the audience were stunned…The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying…I saw kids who had no resources they could draw upon to protect themselves from the dread and fear they felt.”

Those who prefer their horror dealt out as formally as possible might take Night of the Living Dead as camp, but what frightens us most often has that slightly unreal quality, and between its completely un-subtle scoring and sporadic use obtuse camera angles, Night approximates these fears more than efficiently. Barbra is the initial audience surrogate; we may have seen the title of the film, but we know no more than the characters do in regards to what the hell is happening. For her, the unfolding events represent the manifestation of her deepest childhood fears, and for us there is a retroactive similarity to September 11th, with the surviving humans crowding around the television and radio eagerly awaiting updates on the situation (one begs the question: would the Bush administration be able to handle a zombie epidemic, or would we all be as supremely fucked as New Orleans?). But even without these real-world parallels, Night of the Living Dead works its purebred terror without mercy. Says Roger Ebert in his initial coverage of the film: “The kids in the audience were stunned…The movie had stopped being delightfully scary about halfway through, and had become unexpectedly terrifying. There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying…I saw kids who had no resources they could draw upon to protect themselves from the dread and fear they felt.” The film didn’t have quite this much of an effect on my self during my first viewing (a horror buff at a young age, staying up past my bedtime to watch in on the Sci-Fi channel was nothing short of a religious experience, and one of the foundations of my love for film) – by age ten, I was already pretty seasoned in the genre’s gore quotient – but never for a moment have I chalked its violence and gore up to something that can be laughed off. The film shows you just enough tangible violence to inflame the nerves of your imagination, making everything else that is only suggested infinitely more nerve racking (the opening scenes track a car's approach and arrival at a cemetary with distant, static shots, as if suggesting a malevolent presence watching from afar). Night’s half-eaten corpse (eyeball staring outward from the flesh-stripped skull) might not match Dawn’s exploding head opener, yet there’s hardly a thing here that isn’t the stuff of our collective nightmares. Confusion of the unknown largely plays into this fear factor; before news updates reveal that the wave of murders sweeping the country is being compounded by the fact that the killers are eating their victims (who in turn come back to life to continue said behavior), all we and the characters know is that strange human figures are on the prowl with a decidedly unreal lurk about them.

The film didn’t have quite this much of an effect on my self during my first viewing (a horror buff at a young age, staying up past my bedtime to watch in on the Sci-Fi channel was nothing short of a religious experience, and one of the foundations of my love for film) – by age ten, I was already pretty seasoned in the genre’s gore quotient – but never for a moment have I chalked its violence and gore up to something that can be laughed off. The film shows you just enough tangible violence to inflame the nerves of your imagination, making everything else that is only suggested infinitely more nerve racking (the opening scenes track a car's approach and arrival at a cemetary with distant, static shots, as if suggesting a malevolent presence watching from afar). Night’s half-eaten corpse (eyeball staring outward from the flesh-stripped skull) might not match Dawn’s exploding head opener, yet there’s hardly a thing here that isn’t the stuff of our collective nightmares. Confusion of the unknown largely plays into this fear factor; before news updates reveal that the wave of murders sweeping the country is being compounded by the fact that the killers are eating their victims (who in turn come back to life to continue said behavior), all we and the characters know is that strange human figures are on the prowl with a decidedly unreal lurk about them. The film is rightfully credited with forging the mold and “rules” of the modern zombie genre. Zombies are dead humans come back to life (!), zombies need to eat live human flesh (!!), a zombie can be killed by decapitation, killing the brain, or incineration (!!!), and anyone bitten by a zombie will become a zombie in time (!!!!). Ultimately, seven people are held up within the farm house, with the number of flesh-eaters outside escalating by the dozens as the night progresses. As their ranks increase, the humans begin to quarrel over whose in charge and what plan of action needs to be taken: Ben (Duane Jones) wants to stay upstairs, where the zombies’ activity can be monitored and an escape can be made if necessary; Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman) wants to hole up in the basement, an admittedly stronger fortress, but lacking an escape route should the zombies break in. That they are black and white, respectively, is wisely left an ambiguous factor in their antagonism towards each other, but while Romero denies that the racial implications of Night of the Living Dead were wholly unintended at the time, the general state of tension and the ultimate reflection of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination cannot simply be ignored.

The film is rightfully credited with forging the mold and “rules” of the modern zombie genre. Zombies are dead humans come back to life (!), zombies need to eat live human flesh (!!), a zombie can be killed by decapitation, killing the brain, or incineration (!!!), and anyone bitten by a zombie will become a zombie in time (!!!!). Ultimately, seven people are held up within the farm house, with the number of flesh-eaters outside escalating by the dozens as the night progresses. As their ranks increase, the humans begin to quarrel over whose in charge and what plan of action needs to be taken: Ben (Duane Jones) wants to stay upstairs, where the zombies’ activity can be monitored and an escape can be made if necessary; Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman) wants to hole up in the basement, an admittedly stronger fortress, but lacking an escape route should the zombies break in. That they are black and white, respectively, is wisely left an ambiguous factor in their antagonism towards each other, but while Romero denies that the racial implications of Night of the Living Dead were wholly unintended at the time, the general state of tension and the ultimate reflection of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination cannot simply be ignored. If one theme of Night of the Living Dead emerges from all the rest, it would be a general attitude of nihilism towards the state of humanity, a theme that would only continue to escalate in both volume and complexity over the course of Romero’s career. Here, the zombies are an inexplicable “other,” a lightning rod for Vietnam instilled anxieties, but very much an immediate cause for alarm that only underscores the live human’s inability to cooperate in a time of crisis. No cannibalism is committed in the film, but when characters turn on each other in desperate attempts to ensure their own survival, the similarity to the flesh-eating undead is unsettling in no small manner. Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, and Land of the Dead would further these appropriately cynical attitudes, and fans of the series (myself include) debate endlessly as to their comparative worth. Yet there’s something pure and unstoppable about Night of the Living Dead, perhaps a result of it’s incredibly low-budget and the visceral energy that often comes about from such a production. It is the seminal modern horror film.

If one theme of Night of the Living Dead emerges from all the rest, it would be a general attitude of nihilism towards the state of humanity, a theme that would only continue to escalate in both volume and complexity over the course of Romero’s career. Here, the zombies are an inexplicable “other,” a lightning rod for Vietnam instilled anxieties, but very much an immediate cause for alarm that only underscores the live human’s inability to cooperate in a time of crisis. No cannibalism is committed in the film, but when characters turn on each other in desperate attempts to ensure their own survival, the similarity to the flesh-eating undead is unsettling in no small manner. Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, and Land of the Dead would further these appropriately cynical attitudes, and fans of the series (myself include) debate endlessly as to their comparative worth. Yet there’s something pure and unstoppable about Night of the Living Dead, perhaps a result of it’s incredibly low-budget and the visceral energy that often comes about from such a production. It is the seminal modern horror film.Feature: Horror Marathon 2006